Senate Passes FDA Bill

by Jay Bitkower on September 1, 2017Shortly before the U.S. Senate left for an undeserved paid vacation, they passed a flurry of minor bills including funding for the Food and Drug Administration, the FDA Reauthorization Act, by a vote of 94-1, and the Right to Try Act, which enables terminally ill patients to have access to investigational drugs, outside of the clinical trial process. An FDA-funding bill was previously passed by the House, while the Right to Try Act will now move on to the House for consideration.

The FDA Reauthorization Act will retain the user fee, now accounting for a quarter of the FDA’s budget that Congress, passed some years ago requiring the drug companies to pay the FDA in an effort to speed up the approval process of new drugs.

A provision of the Reauthorization Act that was proposed by Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Claire McCaskill (D-MO) promotes generic drug competition and restrains the cost of prescription drugs. “Drug companies should not be able to increase their prices dramatically by thousands of percent overnight without any justification or development of the drug to improve its effectiveness”, said Sen. Collins.

As the chair and ranking members of the Senate Aging Committee, they held a number of hearings last year and issued a report in December 2016 on drug pricing. The legislation is a result of the report. Among other things, the new legislation would:

- Require the FDA to expedite their review of a new generic drug and make a decision with eight months of application when there is insufficient generic competition, specifically three or fewer alternatives.

- Improve transparency of the FDA approval process for generics, such as divulging average approval times.

- Allow the FDA to track the cessation of manufacture of a generic that can result in a shortage of the drug and resultant price hikes, as well as reporting to the public on generics for which there is limited competition.

These are admirable regulations, but how will the new law deal effectively with the problem that was so well defined by the Aging Committee’s December report: “Sudden Price Spikes in Off-Patent Prescription Drugs: The Monopoly Business Model that Harms Patients, Taxpayers, and the U.S. Healthcare System” – see https://www.congress.gov/114/crpt/srpt429/CRPT-114srpt429.pdf.

The report studied the business model of four companies and defined the basic tenets of this model to be the following.

- “Sole-Source. The company acquired a sole-source drug, for which there was only one manufacturer, and therefore faces no immediate competition, maintaining monopoly power over its pricing”.

- “Gold Standard. The company ensured the drug was considered the gold standard – the best drug available for the condition it treats, ensuring the physicians would continue to prescribe the drug, even if the price increased”.

- “Small Market. The company selected a drug that served a small market, which was not attractive to competitors and which had dependent patient populations that were too small to organize effective opposition, giving the companies more latitude on pricing”.

- “Closed Distribution. The company controlled access to the drug through a closed distribution system or specialty pharmacy where a drug could not be obtained through normal channels, or the company used another means to make it difficult for competitors to enter the market”.

- Price Gouging. Lastly, the company engaged in price gouging, maximizing profits by jacking up the price as high as possible. All of the drugs investigated had been off-patent for decades, and none of the four companies had invested a penny in research and development to create or to significantly improve the drugs (emphasis mine). Further, the Committee found that the companies faced no meaningful increases in production or distribution costs”.

So how does this business plan work? The Committee’s first example was a two-month old girl, Isla, who was diagnosed, in 2015, with toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease that will attack the victim’s brain. She was prescribed Daraprim, a 63 year-old drug that would cure the infection within a year. Unfortunately for Isla, the drug price had recently spiked from $13.50 a tablet to $750 a tablet, an increase of over 5000 percent! The yearly cost of the medicine would be $360,000, making it unaffordable for Isla’s family.

As a side note, the drug’s manufacturer is Turing Pharmaceuticals, a company that was headed by Martin Shkreli, who was convicted last month of three counts of securities fraud for his machinations as a hedge fund executive for which he can serve up to 25 years in prison. He was not tried for jacking up the price of a drug as that is not illegal. Nor is the above business plan illegal.

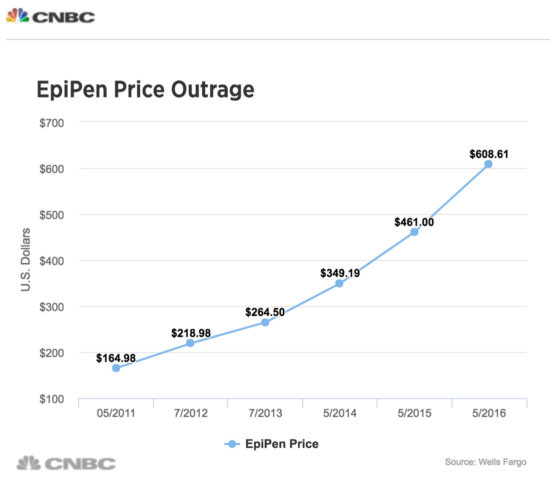

Price gouging is not limited to drugs alone, but also includes medical equipment. One egregious example is the company Mylan Pharmaceuticals, which purchased the distribution rights in 2007 to EpiPen, an epinephrine autoinjector that is used by people with severe, life-threatening allergies, to, for example, peanuts or bee stings. EpiPen, which delivers a pre-calibrated dose to the individual, is sold in pairs since one injection may not be sufficient to prevent a severe reaction. Another company, Sanofi, also had an injectable device but it had to withdraw the product from the market due to a calibration error, leaving EpiPen as the only dispenser available. When Mylan obtained the rights to market the dispenser, the wholesale price was $100 for the two-pen set (the epinephrine dosage costs $1, it’s the pen that injects the exact dosage of epinephrine that is costly). Mylan steadily raised the price of the two-pen sets, so that by 2016, they sold for over $600 a pair. For a school child, the parents need to keep one set at home, one set in the school, and possibly another at grandma’s house. Plus, they expire in a year. After a public outcry, the price has since fallen by half as Mylan has come out with a “generic” version of the EpiPen.

It remains to be seen whether the generic drug provision in the FDA Reauthorization Act will have an effect on the astronomic drug price increases that we have seen in the last couple of years, as the law’s provisions don’t directly address the price of drugs or equipment. According to Bloomberg News, only 2,000 prescriptions of Daraprim are issued each year. At this low rate, it’s understandable why generic drug makers have not entered the market to compete with Daraprim. Even if they do now, which may take up to a year given FDA approval and start-up time, Turing will have made a bundle of money by then, providing an incentive to other companies to follow the same business plan, leading to another outcry about drug prices. The issue will not go away until Congress acts to prevent drug price gouging.

September 05, 2017 at 5:04 pm, Jay Bitkower said:

Sounds good!